By Karen Rubin, Travel Features Syndicate, goingplacesfarandnear.com

Vancouver’s Stanley Park is much like Central Park in New York or Golden Gate Park in San Francisco – an incredibly vast (1001-acre) green oasis in a metropolis. It is absolutely stunning, on a point that juts into the Burrard Inlet and English Bay, with scenic views of water, mountains, sky, the natural West Coast rainforest, and the Park’s famous Seawall.. You can ride a miniature train, rent bikes, go to the Teahouse, take a ride on a horse-drawn carriage, visit the Vancouver Aquarium (65,000 animals, 120 world-class exhibits), walk the many marvelous trails and paths. Most of the manmade structures present in the park– like the lighthouse – were built between 1911 and 1937 by then superintendent W.S. Rawlings. Additional attractions, such as a polar bear exhibit, aquarium, and a miniature train, were added in the post-war period.

But the tranquility of Stanley Park belies its history. The park occupies land that had been used by indigenous peoples for thousands of years – it was one of the most important salmon fisheries in the region and was rich in other resources, including beaver and lumber. British colonizers came in force to British Columbia during the 1858 Fraser Canyon Gold Rush, and extract other resources including lumber. The British then set up military fortifications at Hallelujah Point to guard the entrance to Vancouver harbor (there is still a Navy outpost and the city’s marina).

(A federation of colonies in British North America – New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Quebec, and Ontario – joined together to become the Dominion of Canada on July 1, 1867; Canada only became wholly independent of Great Britain in 1982.)

In 1886, the city incorporated the land and turned it into Vancouver’s first park. It was named for Lord Stanley, 16th Earl of Derby, a British politician who had recently been appointed Canada’s Governor General. Lord Stanley (better known today for hockey’s Stanley Cup) became the first Governor General to visit Vancouver when he came in 1888 to officially open the park.

And that is what brings me together with Patrick, an indigenous guide from Talaysay Tours, who leads me and a woman with her two daughters on a “Spoken Treasures” walking tour of the park.

Patrick says that Indigenous peoples have occupied this area for 8,000 years and there is still a 4,000-year old shell midden within the park. Where Lord Stanley gave his speech was an indigenous burial ground.

Indigenous people who had already been pushed out of their villages in the north had migrated here to the point they outnumbered the settlers, so there was a campaign to force them out or decimate the population. Smallpox was intentionally spread, Patrick says. One way was to inoculate, but not vaccinate people (those who were inoculated could still spread the disease). One cartographer alerted the indigenous people to what was happening.

The park – in fact all of Vancouver – is on “unceded land” – Canada never signed a treaty to acquire it, which means that under Crown and Canadian law, the land is still illegally occupied.

(By way of mitigation, if not restitution, on various websites including Stanley Park, you find a note like this, “The City of Vancouver acknowledges that it is situated on the unceded traditional territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam Indian Band), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish Nation), and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh Nation.”)

There is a marker at Hallelujah Point that describes this place as a thriving settlement which for several millennia was inhabited by the Coast Salish people. From the 1860s, Europeans, Chinese and others built houses and lived along the shoreline. After Stanley Park opened in 1888, the Chinese, who were brought in as laborers and built the park road and the yacht club, were removed; others lived here until evicted in 1931, with the last person leaving in 1957.

Hallelujah Point was taken over as a military fortification to protect Vancouver Harbor and the Canadian Navy still has a small outpost. Patrick says that this was the site of a battlefield with war canoes and was a burial site.

Beaver Lake, one of the park’s major attractions and a place of urban tranquility, “was a sacred site where they brought in beavers,” Patrick said.

Patrick brings us to a grouping of nine Totem Poles, set near Brockton Point and the Brockton Point Lighthouse – considered British Columbia’s most visited tourist attraction.

The collection started at Lumberman’s Arch in the 1920s (originally the village of X’ay’x’ay, which would have had long houses and in 1885, held a great potlatch ceremony attended by 2000 First Nations and European residents of Burrard Inlet), when the Park Board bought four totems from Vancouver Island’s Alert Bay. More purchased totems came from Haida Gwaii (Queen Charlotte Islands) and the BC central coast Rivers Inlet, to celebrate the 1936 Golden Jubilee. In the mid 1960s, the totem poles were moved to Brockton Point. Several of the poles are re-creations, replicas or replacements.

Each has a story.

The Ga’akstalas was carved by Wayne Alfred and Beau Dick in 1991 based on a design by Russell Smith. “We wanted this pole to be a beacon of strength of our young people and show respect for our elders. It is to all our people who have made contributions to our culture,” Beau Dick wrote.

The Chief Skedans Mortuary Pole was carved by Bill Reid with assistant Werner True in 1964 to replace an older version that was raised in the Haida village of Skidegate about 1870, to honor the Raven Chief. The pole has two tiny figures in the bear’s ears to represent the chief’s daughter and son-in-law who erected the pole and gave a potlatch for the chief’s memorial. A rectangular board at the top of the original pole covered a cavity that would have held the chief’s remains.

Patrick isn’t exactly happy with the totem poles being here, which he considers appropriation (exploitation? a balm to soothe a guilty conscience?) rather than a way of raising awareness, respect and honor for indigenous heritage.

A totem pole, he explains, was like legal title to property, marking the land as yours, and would be carved with symbols that basically tell the story of that family.

Only one of the totem poles is legitimately where it should be, he says: the Rose Cole Yelton Memorial Pole of the Squamish Nation, raised in 2009, to honor Yelton, her family and all those who lived in Stanley Park. It was erected in front of the home site where the Cole family lived until 1935. She was the last surviving resident of the Brockton community when she passed away in 2002.

“The Totem was the British Columbia Indians coat of arms,” a bronze plaque reads, using language that might be considered inappropriate today. I had not realized that these poles are unique to the northwest coast of B.C. and lower Alaska. Carved from western red cedar, each carving tells of a real or mythical event. “They were not idols, nor were they worshipped. Each carving on each pole has a meaning. The eagle represents the kingdom of the air; the whale, the lordship of the sea; the wolf, the genius of the land, and the front, the transitional link between the land and sea.”

Such skills, though, had to be resurrected because the government criminalized indigenous art, language and culture, with the intention of eradicating indigenous culture and assimilating the people into Christian society. Because art – the shapes, line and symbols – took the place of written language, the practical effect was cultural genocide.

“Art was criminalized – it is hard to relearn it, but people found other ways to preserve their art,” Patrick tells us. For example, people would make bentwood boxes but weren’t allowed to give them away (that would be considered an illegal potlatch), but could sell them.

“For 100 years, indigenous people were forced into residential schools,” Patrick says. “Oral history made it easy to eradicate. Potlatch, language was criminalized, but people practiced in secret. We have to relearn history.” These house poles, he says, tell the story of that family.

Three beautifully carved, red cedar portals welcome visitors to the Brockton Point Visitor Centre and to the traditional lands of the Coast Salish people. Installed in 2008, the gateways were created by Coast Salish artist Susan Point, in collaboration with Coast Salish Arts; Vancouver Storyscapes (a City of Vancouver Social Planning project to encourage Indigenous people to share their stories through a variety of media); the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations; and the Vancouver Park Board.

“Shore to Shore” carved in cedar then cast in bronze by Stz’uminus Master Carver Luke Marston, is a tribute to the ancestral connection between the area’s aboriginal and Portuguese communities. Joe Silvey came to BC from the Azores around 1860 and married Pqaltanat, a high-born matriarch of Musqueam and Squamish descent, who died; Silvey then married Kwatleematt a Sechelt matriarch who is depicted in the sculpture. The Silvey family lived at Brockton Point in a community of First Nations, Portuguese and Hawaiian people.

Founded in 2002, Talaysay Tours is owned and operated by Candace and Larry Campo, Shíshálh (Sechelt) and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) Nation members. “Our goal is to support culture revitalization, education and reclamation.”

Talaysay Tours, 334 Skawshen Rd, West Vancouver, V7P 3T1, info@talaysay.com, 1 (800) 605-4643, 1 (604) 628-8555, www.talaysay.com.

Salmon n’ Bannock Bistro

From Stanley Park, I take an Uber across a bridge to a neighborhood that reminds me of going to Brooklyn from Manhattan.

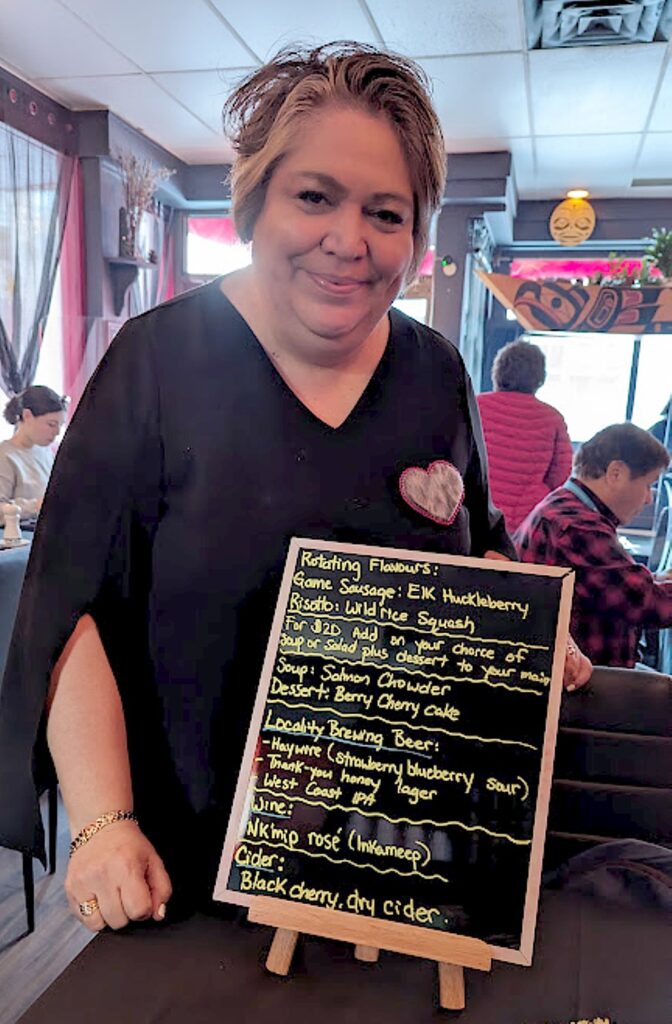

Salmon n’ Bannock Bistro is (so far) the only indigenous restaurant in Vancouver (though Inez Cook, the owner, has just opened a second location at the international departure terminal at Vancouver International Airport).

“It was always a dream,” she tells me – not just to have a restaurant, but to revive and share indigenous culture.

Inez says that like so many of her generation, she was not raised with native heritage.

She shows me a children’s book, “Sixties Scoop,” she has written which describes how she is Nuxalk, born in Bella Coola, BC, but was taken away when she was one year old and adopted by a Caucasian family in Vancouver.

“I am part of what’s called Sixties Scoop, when the government took native kids and adopted them out to non-native families. Our native status was given up and we were supposed to grow up without our culture, without our heritage,” she writes. The “Sixties Scoop” began in the 1950s and lasted until the 1980s.

As an adult, she went to find her native roots and discovered she had a younger sister who was also given up for adoption.

That has made her all the more purposeful in showcasing her heritage with pride. (Inez also serves on the board of the Aboriginal Tourism British Columbia.)

Cook says she was inspired after seeing the Kekuli Café in Kellown, a Canadian Aboriginal bannock restaurant with contemporary twist – bannock, burgers, Indian Tacos, and espresso. (Kekuli Café, which also has restaurants in West Kelowna, Kamloops, and Merritt, BC, has decidedly 21st century marketing techniques including franchising, apps, rewards points and clever slogan, “Don’t panic, we have bannock” https://www.kekulicafe.com).

Cook was raised with the foods of her adoptive mother’s family who were Dutch Mennonite, so when she decided to open an indigenous restaurant, she needed to research native ingredients and First Nations cooking techniques.

“I wanted the restaurant to showcase food from the land and sea that the Indigenous people had traditionally hunted, harvested and eaten – everything from fiddlehead ferns to bison and sock-eye salmon,” she told the BBC. “I wanted to incorporate their traditional methods too: how they smoked food or preserved it over the long winters. I did a lot of asking and learning, then began to improvise.”

“The Olympics was coming. I dove in.” She opened Salmon n’ Bannock in 2010 to offer native cuisine with a modern twist.

Her team is indigenous, the menu based on what’s in season and available. She would ask them, “What’s your favorite dish?” and bring modern inspiration.

Some of the more interesting items on the menu this evening: pemmican mousse with bannock crackers; game sausage (this evening it is elk and huckleberry which is sensational); bison bone marrow served with sage rub and bannock crostini; bison pot roast with mash; smoked sablefish on Haudenosaunee corn polento,. I have the Fish n’ Rice” – wild sockeye with Anishinaabe wild rice.

She will take a native ingredient like soapberries or kelp, or a traditional recipe, and turn it into something new.

Her twist on pemmican, a staple for her ancestors, is an example. The traditional way of serving pemmican was as a mixture of dried meat and berries, which were buried to provide food on a journey. Instead, here the pemmican is made of bison meat, smoked, dried and ground before blending it with cream cheese and sage-infused berries.

Cook worked for airlines for 33 years which enabled her to experience other cultures around the world including Saudi Arabia, India,Egypt, Chad, Nigeria, Indonesia and England, returning to Vancouver in time to open her second 2nd location, at Vancouver airport.

“I’ve lived all over the world- I wanted to take people on a journey to experience the culture of land…Food and culture bring people together,”

She doesn’t miss an opportunity to share the experience and educate. Even the menu features these interesting facts:

- Present day Canada is set on land of 600 indigenous nations, over 200 of them in present day British Columbia. “There’s a cousin behind every corner and a Cree behind every tree.”

- “Indigenous” is an umbrella term that represents First Nations, Inuit and Metis peoples –distinct groups with distinct cultures.

- There are more than 70 indigenous languages, coast to coast in Canada, “many of them endangered due to systemic efforts to separate indigenous people from their culture.”

(I subsequently learn that 1,807,250 Canadians identify as Indigenous, according to the 2021 Census, accounting for 5% of the country’s total population, of which 290,210 live in British Columbia. The population that identifies as Indigenous is the fastest growing demographic group in Canada, increasing by 42.5% between 2006 and 2016.)

For Inez, the restaurant is a chance to show indigenous culture and real people in a contemporary setting, rather than as displays in a museum or separated on a reserve. “We could be your doctor, lawyer, your neighbor,”

It’s an intimate bistro setting – only about eight tables (24 guests) – but its reputation is going global. Time, Elle Magazine have raved and on this evening, seven media people from France have arrived, and Inez greets them in French.

Salmon n’ Bannock Address: 1128 W Broadway #7, Vancouver, BC, 604-568-8971, salmon.n.bannock@gmail.com, www.salmonandbannock.net

I leave the restaurant and have Uber take me to Gastown – with its famous steam clock – to enjoy that nighttime vibe and then take the 15 minute walk back to the Skwachays Lodge just after dark. (Skwàchays Lodge 31 W Pender St Vancouver, BC V6B 1R3 604.687.3589, 1 888 998 0797, info@skwachays.com, https://skwachays.com/)

Indigenous Tourism BC offers travel ideas, things to do, places to go, places to stay, and suggested itineraries and a trip planning app (https://www.indigenousbc.com/)

Next: Trail to Discover British Columbia’s Indigenous Heritage Goes Through Whistler-Blackcomb

See also: ON THE TRAIL TO DISCOVER VANCOUVER’S REVIVED INDIGENOUS HERITAGE

_____________________________

© 2023 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com, www.huffingtonpost.com/author/karen-rubin, and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Visit instagram.com/going_places_far_and_near and instagram.com/bigbackpacktraveler/ Send comments or questions to FamTravLtr@aol.com. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/KarenBRubin