By Karen Rubin, Travel Features Syndicate, goingplacesfarandnear.com

Colmar, in France’s Alsace-Lorraine region, is a storybook village – its buildings literally decorated to tell a story. And when you wander around its narrow, twisting streets, you walk through 500 years of history, lose all sense of what century you are in and fall totally under its spell.

Almost miraculously, the city has managed to remain mostly unscathed through centuries of wars. So as you stroll around, you come upon architectural jewels from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. (You can follow a self-guided historic walking tour of silver Statue of Liberty figures in the pavement.)

I became curious about visiting Colmar when I saw a short report about it being the childhood home of Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, the sculptor who created the Statue of Liberty, and the images of how colorful and charming it was. I had to see if for myself.

So I take advantage of the ease of visiting Colmar from Strasbourg, the starting point for a European Waterways canal cruise through the Alsace Lorraine on its luxury hotel barge, Panache. It is just 45 minutes on the train, every half hour, a most enjoyable, comfortable and scenic ride, 28E roundtrip, no need to reserve – and join the hordes of day-trippers exploring this fairytale-like place.

It’s a short, pleasant walk from the Colmar train station into Le Petit Venise (Little Venice), the historic district (really similar to Strasbourg’s Le Petit France), and I am immediately enchanted.

Colmar is famous for its half-timbered houses and richly decorated merchants’ mansions. Some date from the Middle Ages, such as the Adolf House, the oldest in Colmar, built in the second half of the 14th century; and the “Huselin zum Swan” on Schongauer Street.

The Renaissance is on display in one of Colmar’s most magnificent structures, Maison Pfister with ornate bay windows (oriels), long wooden gallery and exquisitely painted murals, which has become a symbol of the city. Maison Pfister was built in 1537 for Ludwig Scherer, a wealthy hatter from Besancon. The paintings that decorate the façade, attributed to Christian Vacksterffer, represent 16th century Germanic Emperors, Evangelists, Church Fathers, allegorical figures and biblical characters and scenes. It is named for the merchant Francois-Xavier Pfister who acquired the mansion in 1841.

I come upon a house at 34, rue des Marchands with a plaque dated 1435 and a note that says this was the residence of master painter Caspar Isenmann “(Zum Grienen hus”). Another marvelous structure is “Cour du Weinhof,” at 12-16 rue des Marchands, which is a medieval 14th century granary.

So many of the buildings are adorned with beautiful, even playful, whimsical decoration – as if there is a competition for who can have the prettiest or cleverest or most festive, or perhaps a public ordinance that requires everyone to be incredibly festive and clever. I wonder.

I go in search of the intriguingly named House of Heads. Built in1609 in German Renaissance style, it has a three-story bay window, and a façade embellished with 111 heads and masks.

You walk through a fabulous pedestrian zone -a listed “protected sector” – that takes you from the Middle Ages to the 18th century, from “Little Venice” to the Tanners district with its grand white-fronted houses.

Similar to Strasbourg, there are districts, or neighborhoods, built around trades.

The Poisonnerie quay where fish caught mainly in the River Ill were stocked and sold, dates from the 14th century. Part of this district was damaged in a major fire in 1706 but some houses were rebuilt. The whole area underwent urban revitalization from 1976 to 1981.

The Tanners Quarter, rounded by the Rue de Montagne Vertne, Rue des Tripiers, Rue des Tanneurs and place de l’Ancienne Douane, is the epicenter of the protected old town center. Its tall, timber-framed houses built during the 17th and 18th centuries, often have a final open-worked level which was used by craftsmen to dry their pelts. The district was restored 1968-1974.

The Koifhus (Old Customs house) completed in 1480, is the oldest public building in the city. The ground floor was used as a warehouse, where imported and exported goods were taxed. The floor was used for meetings of the deputies of the Décapole, the federation of the 10 imperial cities of Alsace, formed in 1534 and for the Magistrate. When the Revolution abolished commercial privileges, the building was used for other purposes. Around 1840, the building was used as a theater and in 1848, the first office of the discount bank. The Koïfhus was occupied by the Chamber of Commerce and Industry from 1870 to 1930 and by a Catholic boy school and an Israelite school in the late 19th century. Today it is used for various public activities.

A marvelous place is The Covered Market, especially to pick up picnic fixings for lunch or snack. Designed in 1865, this building is made of bricks, with a metal frame has had several functions until being returned to its original purpose of market hall. About 20 merchants offer high quality products: fruits and vegetables, butchery, cheese dairy, bakery and pastry, fish and other terroir delights – yet another example of what is old becoming new again. (13 rue des Ecoles, Quartier de la Petite Venise).

I find a sensational patisserie that has the best croissants, which I munch just outside in a tiny park.

Musee Unterlinden

I wander a bit aimlessly, just soaking in the atmosphere, and find myself at one of Colmar’s most important museums, Musee Unterlinden.

Founded in 1906, Musee Unterlinden is housed in a 13th century convent building that was linked to the former municipal baths building by architects Herzog & de M Meuron, who added a contemporary extension. Within you wander through 7,000 years of history, culture and art from the prehistoric era to 20th century.

The museum is mainly known as a showcase of Rhenish Art, displaying a remarkable collection of paintings and sculptures of the Colmar region of the 15th and 16th centuries, a Golden Age for the Upper Rhine.

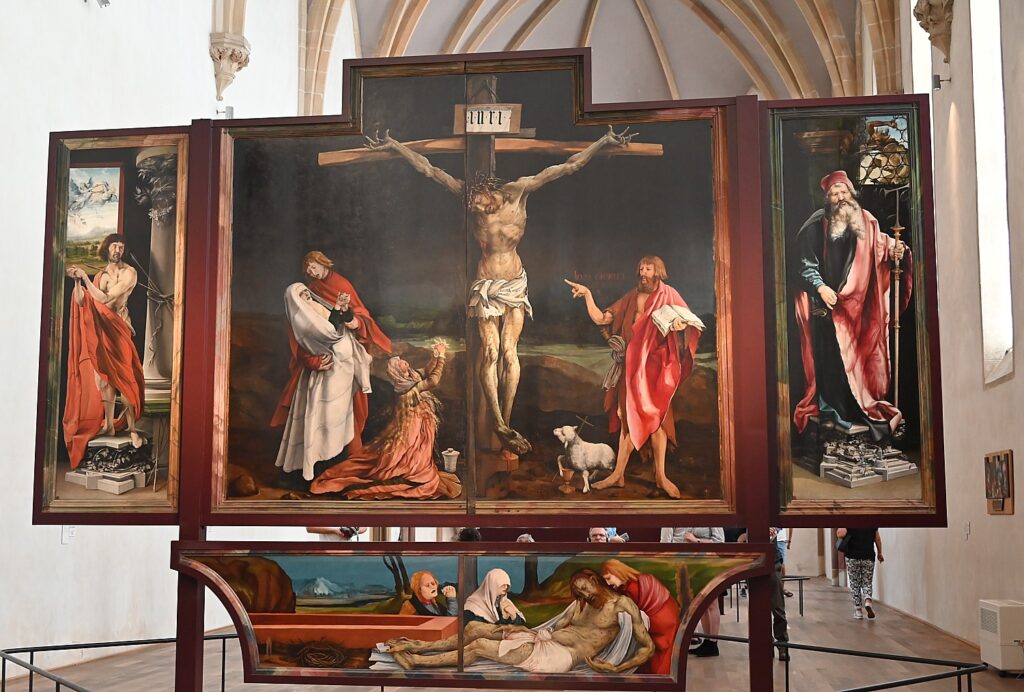

But its star attraction is the celebrated altarpiece of Isenheim, an exquisite polyptych created between 1512 and 1516 by the artists Niclaus of Haguenau (for the sculpted elements) and Grünewald (for the painted panels). It was created for the Antonite order’s monastic complex at Isenheim, a village about 15 miles south of Colmar, where it decorated the high altar of the monastery hospital’s chapel until the French Revolution.

The Isenheim Altarpiece is housed in the museum’s Medieval cloister, where you find the art of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, with works by Martin Schongauer, Hans Holbein and Lucas Cranach. The former baths building that opened in 1906 is used for special exhibitions, while the works of major 20th century artists including Monet, de Staël, Picasso and Dubuffet have a new showcase in the contemporary wing.

I wander down to the cellar of the former convent, and am fascinated to see its extensive archaeology section, with artifacts of the Haut-Rhin region dating back thousands of years. The collection has been expanding because of ongoing regional excavations. One section is devoted to prehistory and protohistory, the neighboring rooms to the Roman and Merovingian periods.

The extensive collection of historical objects and artifacts from domestic life and funerary contexts, mostly from the northern Haut-Rhine, presents an almost complete overview of the different stages of the region’s cultural evolution.

I find it interesting to learn Unterlinden was founded by a man who was convinced of the importance of “making a contribution to forming and developing a sense of taste and beauty” and of “providing the lower classes with an opportunity to benefit from the knowledge and pleasures they are so often denied.” In 1847, Louis Hugot, archivist and the city librarian of Colmar since 1841, was inspired by his love of graphic art to establish the Martin Schoengauer Society with other local scholars. Two years later, the society published its plan to transform the Unterlinden Convent into a museum.

Musee Unterlinden, Place Untrlinden, https://www.musee-unterlinden.com/en/home/.

Musee Bartholdi

The climax for my enchanting tour of Colmar comes when I (finally) find my way to the Musee Bartholdi (I seem to have overshot it a couple of times, even though everything is really close, even though there are metal markers in the street leading to the museum). The museum is housed in the childhood home of sculptor Frederick Auguste Bartholdi (1834-1904), who created the statue we know as the Statue of Liberty, but was actually named “Liberty Enlightening the World,” unveiled in New York in 1886.

Bartholdi was the son of a councilmember who died in 1836 when he was just two years old. The family residence was built in the 15th century and transformed in the 18th century into an elegant hotel particulier (town mansion).

When Bartholdi died, his widow defied his wishes (he wanted her to create a museum for sculpture) and turned his Colmar family home into a museum as a tribute to him. Opened in 1922, the Bartholdi museum is entirely dedicated to presenting the artist’s work as well as his process, so you see models, drawings, engravings and photographs. You also see family furniture and personal mementos.

You enter through an inner courtyard, where you see Bartholdi’s inspiring statue, “Grand soutiens du monde” – four women holding up the world (bronze 1902).

The collection is presented on three floors of the mansion and walking through the family’s rooms lets you see Bartholdi as a person, how his idealism was manifested in his art, and you realize that his true genius is how his art inspires that same idealism in the viewer.

A whole room (surprisingly small, but that makes it more intimate) is dedicated to the Statue of Liberty – you see his inspirations and some early designs, and fantastic historic photos of its production in Paris. It is thrilling to see Bartholdi’s process for the Statue of Liberty, which he titled Liberty Enlightening the World.

Indeed, Bartholdi’s colossal Lady Liberty famously celebrates freedom, and most Americans believe his symbols refer to the American Revolution and independence from tyranny, especially since it was dedicated in New York 1886, a little over a century after the Declaration of Independence. But Bartholdi intended Liberty to commemorate America’s abolition of slavery as a result of the Civil War in 1865 – the idea for the monument originated in 1865 but was pursued only after the Third French Republic was established in 1870. We see a model of the statue that has Lady Liberty’s foot stepping on chains, as if to crush the chains of bondage.

Lady Liberty stands 151 feet tall, and the top of her torch brings the statue up to 305 feet – the largest statue that had ever been completed up to that time.

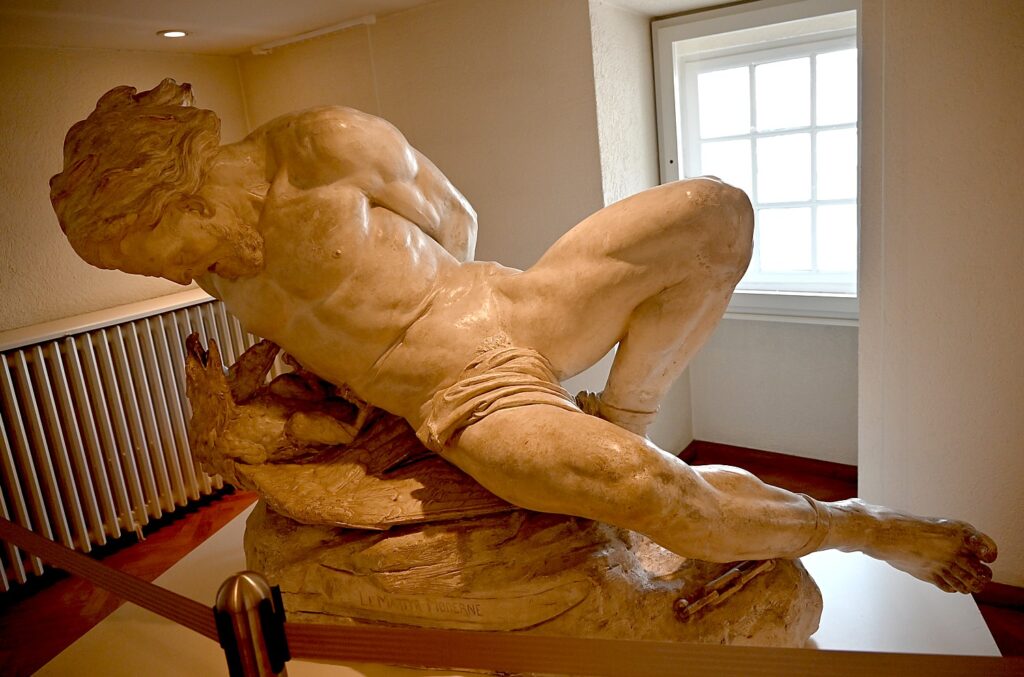

There are also his models for Bartholdi’s monumental statue, Lion of Belfort, which is as precious to France as Lady Liberty is to America. Bartholdi served in the Franco-Prussian War and took part in the defense of Colmar. I read that Bartholdi was distraught over Alsace’s defeat and over the years, constructed monuments celebrating French heroism in its defense against Germany. Lion of Belfort, which he created from 1871-1880, symbolizes the French resistance against Prussia’s assault during the 103-day Siege of Belfort, December 1870 to February 1871.

Colmar had always celebrated its native son, Bartholdi, and he had erected statues in the city, including his earliest works. But in the 1890s, German authorities restricted Bartholdi’s residency permit in Alsace, because several of his public monuments demonstrated support for a French Alsace. The sculptor found it increasingly difficult to travel to Colmar. In light of this, the Schoengeuer Society’s decision to set up a Bartholdi Room in the Unterlinden Museum in 1898 was a courageous move.

Bartholdi collaborated with the Schoengauer Society early on – his first major sculpture was created for the Unterlinden Museum when he was just 18 years old – a plaster statue of the founder of the Unterlinden Convent, Agnes de Hergenheim (1852), as well as the monumental fountain in honor of Martin Schongeuer, erected in the cloister of the former convent (1863). Bartholdi donated several works to the society which were transferred to the Bartholdi Museum when it opened in 1922.

Following the re-annexation of Alsace and Moselle by Nazi Germany in June 1940, Colmar was once again under German rule. The museum was shut down. The German forces destroyed Bartholdi’s monuments in the city – the statue of General Rapp was smashed on September 9, 1940; the Bruat fountain was dismantled. Figures of the four continents in red Vosges sandstone were crushed.

But some Colmar residents managed to get to the site to save the four heads and a part of the foot, which they hid in their cellars. The fragments were returned to the city after the war (they are on view in the museum) and a new version of the fountain was erected in 1958.

The museum reopened in 1979, very likely spurred by preparations for celebrating the Statue of Liberty Centennial.

(We can see his works in the United States also: Marquis de Lafayette in Union Square, NYC; Bartholdi Fountain in the Botanic Garden, Washington DC.)

There is also a 12-meter high replica of the Statue of Liberty, sculpted to commemorate the 100th anniversary of sculptor Auguste Bartholdi’s death, located at the northern entrance to the town.

The museum has a brochure (in French) with a map of where you can find Bartholdi statues and monuments around Colmar: Monument du Général Rapp – 1856 (first shown 1855 in Paris. Bartholdi’s earliest major work); “Fontaine Schongauer” – 1863 (in front of the Unterlinden Museum); “Fontaine de l’Amiral Bruat” – 1864; “Fontaine Roeselmann” – 1888; “Monument Hirn” – 1894; “Fontaine Schwendi”, depicting Lazarus von Schendi – 1898; Les grands soutiens du monde − 1902 (statue in the courtyard of the museum).

(Musee Bartholdi, 30 rue des Marchands, 68000 Colmar, https://www.musee-bartholdi.fr/)

Another site I miss is the Synagogue. Built 1839-1842 on the site of an old farm, the synagogue of Colmar is the seat of the Israelite Consistory and the Grand Rabbinate of the Haut-Rhin.

I learn that the Jewish community was expelled in the 16th century, but returned to Colmar during the Revolution. The Rabbi was transferred from Wintzenheim to Colmar in 1823. The synagogue of Colmar was renovated in 1885 and an annex added in 1936. Used as an arsenal during the German occupation, the synagogue was restored after the war. It is the only synagogue in the region which has a bell tower. (3 rue de la Cigogne,)

Unfortunately, I leave Colmar before seeing its Illumination. The town is illuminated from nightfall on Fridays and Saturdays year-round and every evening during major events in Colmar such as the International Festival, Regional Alsace Wine Fair and Christmas in Colmar.

Another reason to look forward to returning.

For more information about Colmar’s museums: https://www.tourisme-colmar.com/en/visit/presentation/museums

For more visitor information, contact Tourist Office of Colmar, Place Unterlinden, +33 (0)3 89 20 68 92, info@tourisme-colmar.com, https://www.tourisme-colmar.com/en. The website is really helpful for planning: https://www.tourisme-colmar.com/en/visit/presentation/discover

See also:

DISCOVERING STRASBOURG FRANCE’S CULTURAL RICHES

TIME-TRAVELING THROUGH STRASBOURG IN FRANCE’S ALSACE-LORRAINE

_______________________

© 2024 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Visit instagram.com/going_places_far_and_near and instagram.com/bigbackpacktraveler/ Send comments or questions to FamTravLtr@aol.com. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/NewsPhotoFeatures