A century after the Confederacy’s rebellion, slavery’s legacy was still strong.

On March 7, 1965, images of over 600 protesters being brutalized by police in Selma, Ala., were broadcast. The images shocked the public and reignited the fight against racial injustice.

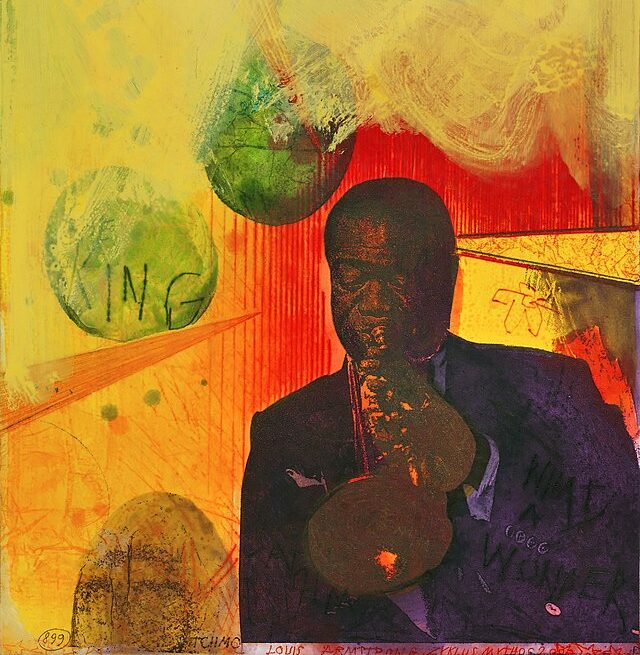

Louis Armstrong, the legendary jazz musician, was among those questioned by the media afterward. As he prepared to begin his first tour behind the Iron Curtain, reporters asked why he did not take part in such marches.

“I don’t march, but I send my contributions to the Negro organizations. Let the others march,” he said. “They would only smash my face so that I could not use my trumpet.”

When asked if a man of his stature would be beaten, Armstrong responded, “They would beat Jesus if he was black and marched.”

Armstrong’s stories, including this one, were told at the Port Washington Library Friday afternoon. It was part of the Juneteenth celebrations at the library.

Juneteenth commemorates the day in 1865 that enslaved African-Americans in Texas learned more than two years later that the Civil War was over and that they were now free. It has also developed into a day commemorating black history and a federal holiday.

Ricky Riccardi of the Louis Armstrong House Museum in Corona, Queens, was the guest lecturer. He followed the presentation with a Q&A session.

He pieced together Armstrong’s life using rare footage, audio and images. The presentation focused on the battle between his fame and America’s racial challenges.

“The smile, the Louis Armstrong smile, was so misunderstood here,” said Riccardi. “African-Americans started calling him ‘Uncle Tom,’ and said he was just smiling for the white people. That smile makes him absolutely beloved overseas.”

Beginning in 1956, the State Department began hiring prominent American jazz musicians like Armstrong as “ambassadors” for the U.S. abroad. They did this to improve the United States’ public image in the wake of Soviet Union criticism.

“In November 1955, in The Sunday New York Times, (Washington reporter) Felix Belair published the article, ‘United States Has Secret Sonic Weapon–Jazz,’” Riccardi said. “And it begins ‘America’s secret weapon is that blue note in a minor key. Right now, it’s most effective ambassador is Louis (‘Satchmo’) Armstrong.’”

In September 1957, Armstrong spoke out against racial injustice at Little Rock, Ark. The Arkansas governor had dispatched the state National Guard to prevent nine African-American students from integrating Central High School.

“The way they’re treating my people in the South, the government can go to hell,” he told a reporter.

Days later, President Dwight Eisenhower dispatched federal troops to Little Rock to ensure that the students arrived. Many believed Armstrong’s statements inspired him to act.

Yet in the wake of his remarks, his contemporaries did not support Armstrong, even as white reporters heavily criticized him. He was later encouraged to avoid speaking out.

Riccardi said that as Armstrong silenced his public voice, he stood by his views and ideas in private.

“Today, nearly 50 years after he passed, it’s a completely different story and the main reason is because of Louis Armstrong himself,” he said. “By maintaining a personal archive, Armstrong made sure that he would be in charge of telling his own story to future generations.”

As he made his Selma March remark, Armstrong temporarily suspended his silence policy. Once his Iron Curtain tour began, he avoided commenting on the subject. However, he started singing an older song of his, “(What Did I Do To Be So) Black & Blue?” to express his beliefs.

“He had stopped doing it for a while. But on this Iron Curtain tour, he brought it back out and performed it every night, usually with a deadly serious expression. He also changed one of the lyrics,” he said. “The original lyrics was ‘I’m white inside, but that don’t help my case,’ and Armstrong now began singing ‘I’m right inside.’”

Then he resumed his pre-Selma approach. Everything changed for Armstrong after a near-death experience with heart and kidney problems in 1969.

“He ended up in intensive care for the second time and he thought he was going to die,” said Riccardi. “So he grabbed a notebook and began basically spewing all the hate and just the misery that he had. He felt betrayed.”

Other black musicians stepped forward to express their love for him after nearly losing him. They assisted him in the making of his last album, “Louis Armstrong and His Friends,” in 1970.

Riccardi said this moment was Armstrong’s emotional high, which included recording the song “We Shall Overcome.” It had deeply affected him when he heard the song performed at Martin Luther King Jr.’s funeral.

“Nobody had to overcome more than Louis Armstrong to get where he was,” said Riccardi. “And like I said, people changed their minds a little bit before he died.”

Armstrong was 69 when he died in 1971.

Lucille, his wife, took up proving who he was to the public by saving all of his recordings, scrapbooks and writings.

Riccardi said in an old blog post that learning about Louis’ life would have been impossible if it hadn’t been for “the gifts Louis and Lucille left for us.”

Anyone interested in learning about the Louis Armstrong House Museum can do so by visiting its website.