The history of politics in the 20th century reflects the ascendancy of political propaganda, which helped fuel the social movements that defined the course of human events beginning with the era of the First World War.

The rise of fascism under Franco in Spain, Mussolini in Italy and Hitler in Germany are among the most obvious examples of political forces fueled by manipulations of mass perception. But the earliest conspicuous examples of carefully conceived ideas intended to push popular opinion in a particular direction are the posters born in the imaginations of Ilych Lenin’s artistic collaborators during the Russian Revolution.

Prime examples of the resulting artwork are in the current exhibit of posters at the Nassau County Museum of Art, on loan from the Arnold A. Saltzman Family Collection through May 8. The exhibit provides an alternately dramatic and comedic literal montage of what the Bolsheviks used to communicate their communist concepts to the largely illiterate populace of provincial Russia.

Lenin’s idea, taken from the writings of Karl Marx, was to heighten the awareness of oppression of the ruling class among the working class, to explode the concepts they had previously accepted about religion and the prevailing social order.

“The worker,” Lenin said, “will not be able to get this true picture from books; he will not find it in current accounts, in still-fresh explanations of things happening at any given moment, about which we speak or whisper among ourselves and which are reflected in such-and-such facts, figures, verdicts, etc. These political revelations, embracing all spheres, are the necessary and fundamental condition to preparing the masses for their revolutionary activity.”

Posters, produced en masse and posted in public places, were a cheap and efficient way of delivering the Bolshevik party line on a range of subjects to all citizens of the fledgling Soviet republic during its formative stages as its revolutionary movement progressed. They were created by some of the foremost Russian artists of the time, including Dmitry Moor and Victor Deni, and the current display of their works at the Nassau County Museum provides a compelling encounter with images that wielded the power to transmit ideas that ultimately transformed Russia from monarchy to another form of fascism in a way that reverberated through the world.

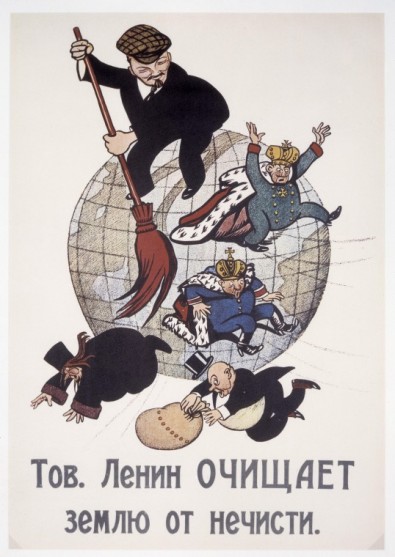

Deni’s viciously satirical image of Lenin “sweeping the garbage off the face of the earth,” as it is captioned in Russian, shows a vividly colored cartoon figure of Lenin standing on the globe with a broom in his hand, brushing caricatures of two monarchs, a fat capitalist and a Russian cleric away like so much rubbish.

Calls to arms, calls to end illiteracy and to improve the social status of women were among the subjects the posters addressed.

A poster reminiscent of World War I recruitment posters shows a Red Army soldier, a rifle in on hand, pointing to the viewer and asking “Have you enlisted with the Reds?”. It intended to draw Russians into the civil war against the counter-revolutionary White Guards.

Another poster showing a red knight slaying a white dragon conveyed the same sense of counter-revolutionary crusade.

A poster circa 1920 shows a knightly figure bearing a torch and a book astride a winged horse, suggesting Pegasus of Greek mythology, delivering a very different message: “Reading and Writing – The path to communism.”

Some posters are rendered in black and white with a gritty realism extolling the heroism of the armed struggle, such as Alexander Aprit’s depiction of soldiers with bayonets fixed, captioned “Chests forward in the defense of Petrograd.”

Perhaps the most haunting image of the collection is Dmitry Moor’s black-and-white rendering of a wizened white figure with arms upraised in a gesture of supplication, over the caption “Help!” meant to inspire donations to aid 30 million Russians in danger of starving during the famine of 1921.

The contrast in styles between posters lauding the idyllic aspirations of the revolution and those conveying the urgency of specific aspects of the Bolshevik social and economic agenda are most striking. The images are not subtle, intended to hit the viewer between the eyes, so to speak, rather than inspire discourse on the finer points of Marxist theory.

“You! Still not a member of the cooperative?” blares one caption under a drawing of an old man with his finger pointed at the observer on a poster bearing an uncanny resemblance to Uncle Sam in American recruitment posters.

Another latter day piece of Soviet propaganda depicts a virtuous worker reaching his hand down to raise up a Russian woman, over the caption “Having destroyed capitalism, the proletariat will destroy prostitution.”

The overriding spirit of Lenin’s cause, aimed at spawning a worldwide workers’ revolt, is also evident in this display of wide-ranging, propagandistic imagery. An angelic figure in a flowing robe drops flowers over a crowd of workers marching with banners raised, over the message, “Long live workers of all countries,” in one poster.

These were the earliest efforts to represent the Russian Revolution as an idealized exercise in social dynamism embodying the most ennobling aspects of the human spirit in the communist vernacular. The reality, of course, in the purges of Lenin and the megalomaniacal Josef Stalin, revealed a far different picture. But propaganda never stopped.

When George Orwell returned from fighting with the loyalists in Spain against Franco’s fascists, he noted with unabashed irony reports in British newspapers of loyalist atrocities committed in battles that he knew from his experience in the trenches had never taken place.

He also knew that Stalin’s efforts to aid the anarchist-grounded revolt in Spain were intended to sabotage a revolution that the Soviet dictator couldn’t tolerate because he hadn’t planned it. The communists denounced the Spanish anarchists, and the revolution fell apart as the western powers joined the Nazis and Italian black-shirts to support Franco.

“History stopped in 1936,” Orwell told his friend, novelist Arthur Koestler, who famously exposed the indoctrination of victims of the first Stalinist purges in “Darkness At Noon.”

Orwell’s invention of a future characterized by propagandists who routinely alter history in “1984” was a warning to a literate society that is now inundated by the inventions of what we benignly call “spin doctors.”

But the first blush of unvarnished propaganda that prefigured Orwell’s bleak vision is hanging on the walls of the Nassau Museum of Art through May 8 in a sobering, provocative exhibition.