It had been 35 days since her son’s funeral, a solemn end to his six-year addiction to heroin and prescription drugs Oxycontin and Xanax, a mother named Lee told a mostly filled auditorium at Herricks High School on Monday.

She had just arrived home from the store, where she bought warm clothing and anything else the young man might need during his latest attempt at detoxification and sobriety, when she said her mother’s intuition told her to drop everything and go upstairs.

She found him lying on the bathroom floor, his skin turned blue – overdosed and cold before she could reach for her Narcan kit and revive him, much less call an ambulance.

“By then, it was no use,” she said through tears. “He was already gone.”

The tale jolted one of the first Nassau County-sponsored Narcan training seminars of 2015, a harrowing reminder of addiction cutting deeper than the troubled people seeking an escape from life’s struggles.

Lee said she probably couldn’t have saved her son because he was alone when he used for the last time. Text messages she later found in his cell phone hinted that his overdose was meant to be fatal.

But the mere presence of Narcan in her home, and Lee’s ability to use it, reflects a changing of the guard in the way New York State has approached the distribution of the revival agent amid spiking opioid use across America.

In 2006, the state Legislature approved a law clearing non-medical professionals of liability in using Narcan on a person suspected of overdosing. It passed two more bills in 2011, one establishing a registry to document monitor patients who fill opioid prescriptions and another decriminalizing misdemeanor drug possession for people who call 911 to assist an overdose victim.

In 2012, Nassau County became certified in the state’s overdose responder program, enabling its Office of Mental Health & Chemical Dependency to offer free Narcan certification clinics and information sessions amid record fatal heroin and opioid overdoses that year (154). There were even more, 159, in 2013, but fatal opioid overdoses dropped to 87 in 2014, according to county statistics.

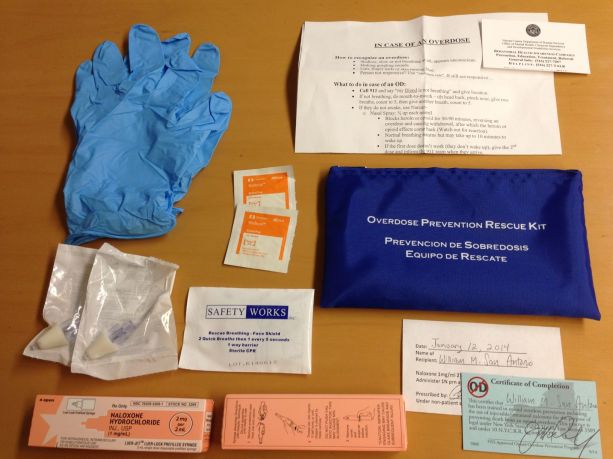

Residents who attend the sessions are eligible to receive certification to administer Narcan, also known as Naloxone, and receive free kits provided by the county, which include two doses of the drug in the form of a nasal spray. Narcan may also be administered through injection.

“[Heroin and opioid use on Long Island] is the worst I’ve ever seen,” said Lorretta Hartley-Bangs, a social worker with the North Shore-LIJ Health System’s Community Treatment Center in Mineola who spoke during a panel discussion about Narcan Monday.

County health officials at the sessions teach attendees the warning signs of a potential overdose, which include uncontrollable nodding, an inability to respond to stimulation, heavy gurgling or gasping for air and skin, lips and nails that turn blue in color.

Attendees are also taught an eight-step process to administering Narcan that begins with attempting to stimulate the potential overdose victim, calling 911 and conducting CPR before using the revival drug.

A revived overdose victim will often immediately feel withdrawal symptoms and want to use again, so officials tell seminar attendees to let them know emergency medical technicians are on their way.

“It’s frightening to see your child on the ground, not breathing. You may forget how to dial 911, but that’s what we’re here for, to talk you through it,” said Mike Seltzer, president of the Nassau County Police Medic Association.

If both doses of Narcan have been used, county officials tell attendees to contact the Office of Mental Health & Chemical Dependency to receive additional doses, rather than purchase them from local pharmacies.

The county also keeps records of overdoses in which Narcan is administered.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, about 10,000 instances have been reported across the country since 2006.

Update (8/31): Lee said Monday her son did not intend to kill himself, as text messages in his phone indicated he meant to use just enough so he would not overdose, as he had just gotten clean. She also said she found him on his bedroom floor, not the bathroom, and that his skin had not turned blue. Her son was also awaiting entry to a treatment facility, she said.