Time is money when it comes to construction, local school officials say.

As they plan and start large building initiatives, some North Shore districts are worried long delays in state reviews of their projects could mean they will end up costing more, or require planners to trim them to stay within their budgets.

“The biggest issue with the delay is you estimated the cost with old money,” said Michael Nagler, superintendent of the Mineola school district. “… The longer you wait, the more problematic that is.”

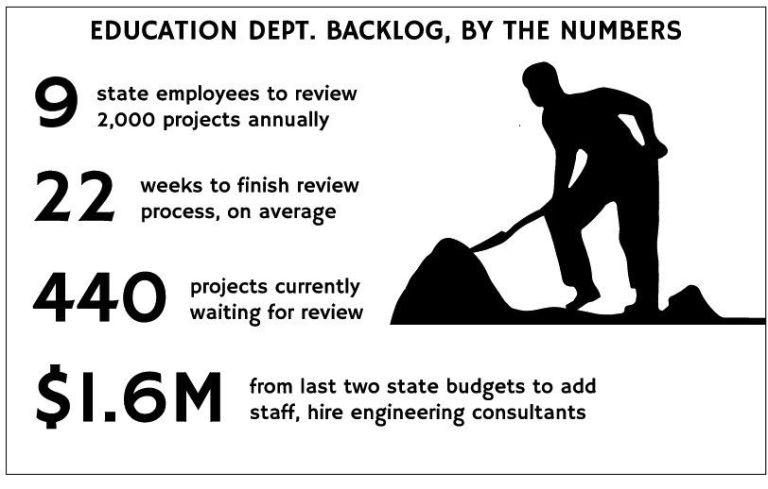

The state Education Department on average takes about 22 weeks to review school building projects, a department spokeswoman, Jeanne Beattie, said in an email. An influx of projects in recent years has left the department’s staff of nine to review about 2,000 projects annually, Beattie said.

Seven North Shore school districts — East Williston, Great Neck, Manhasset, Mineola, Port Washington, Roslyn and Sewanhaka — have projects waiting for state approval, state records show. Final plans for some were submitted as early as February 2015, records show.

Helped by extra funds, the department has hired outside engineers to help and taken other steps to cut the wait time from nearly 11 months earlier this year, Beattie said. About 440 projects are awaiting reviews, according to the department’s facilities planning office.

But construction gets more expensive as districts wait, meaning they must build financial cushions into their multimillion-dollar capital plans, superintendents said.

“Not only is it a delay in seeing these projects come to fruition, but it may end up costing districts more money in the end because of the fact that the cost of construction is escalating,” said the Herricks school superintendent, Fino Celano.

Projects awaiting final state approvals include repairs at eight Port Washington buildings, electrical work throughout the Great Neck district and $5 million worth of work at Mineola’s Hampton Street School.

The Education Department reviews all projects for safety and compliance with codes and regulations, Beattie has said. Once it’s submitted to the state, each project must get approvals for project management, architecture and engineering, she has said.

The first two can take between a day and a week to complete depending on the complexity of the project, Beattie said.

Engineering reviews — the source of the backlog — closely examine electrical systems, ventilation, plumbing, lighting and other details, a more complex process that generally takes a week or more, Beattie said.

Herricks administrators must consider the delay as they plan $25 million worth of work across the district’s seven buildings, Celano said. They want to hold a bond referendum in December but don’t expect any projects to be done until at least 2018, he said.

Costs for materials, wages and pensions rise regularly, so project budgets can be right one year and off base the next as districts wait for approval, said Mitchell Pally, chief executive officer of the Long Island Builders Institute.

“There is no question that in many cases in a construction environment, the longer you wait to build, the more expensive it will be,” Pally said.

One architect told Celano construction costs are rising as much as 10 percent annually, so administrators have accounted for cost increases in the $25 million plan, he said.

The Mineola School District is waiting for the start of the engineering review for the Hampton Street School projects, which includes an overhaul of the athletic field where Mineola High School’s football team plays. The district also submitted plans in May for air conditioning in classrooms at Jackson Avenue School and the expansion of classrooms at Meadow Drive School, funded by Mineola’s 2016-2017 budget.

Construction costs have increased since the district first submitted plans for the work at Hampton Street, which voters approved in November 2015, Nagler said. It may have to trim parts of the project to fit its budget when it asks builders for bids in the fall, Nagler said.

Asking contractors to bid on a base package of work that must be done and separate optional pieces called “add-alternates” can help districts keep to their budgets, said Ralph Ferrie, superintendent of the Sewanhaka Central High School District.

Sewanhaka did that for the third phase of an $86.6 million capital initiative, which includes auditorium renovations at three of its five schools and an addition to Sewanhaka High School.

“You have to make some decisions in order to build what you said you were going to build,” Ferrie said. “It’s almost like when you go in and buy a car — if you want to have every single upgrade on the car or you want to start paring back. The car will still get you where you need to get.”

While school construction projects are generally smaller in scale and require fewer workers than they used to, Pally said, the state backlog could have an impact on construction jobs.

The industry accounts for about 10 percent of Long Island’s gross domestic product, Pally said. State labor statistics show it added about 3,200 jobs on Long Island between June 2015 and June 2016, but it has seen “up and down” employment patterns in recent years, Pally said.

“When these jobs don’t start, that would keep some people off the unemployment rolls,” said Richard O’Kane, president of the Nassau-Suffolk Building Trades Council. “If you have a couple of hundred [people] working on a school project, think about maybe 50 or 60 or 100 have to stay out of work longer because they couldn’t get on that job.”

Long Island superintendents’ groups have suggested the state let districts pay a fee to get projects into a special expedited queue, Nagler said. It could also let districts hire their own engineers to do reviews, Ferrie said.

The Education Department’s project review staff is about half what it was a decade ago, Carl Thurnau, the state’s director of facilities planning, told the New York State School Boards Association in an April 2015 article.

The department has hired nine outside engineering firms to help with project reviews and is in the process of hiring more permanent staff using a combined $1.6 million boost in the past two state budgets, said Beattie, the department spokeswoman.

The state also speeds up reviews for certain emergency projects and has streamlined reviews for simple work, such as replacing equipment, so it can get approved within a few weeks.

School districts should make sure they submit complete plans so the process runs as smoothly as possible, Thurnau wrote in a January newsletter.

“We are aware of the practice of submitting incomplete work as placeholders due to the backlog, and we understand the backlog has made this situation worse,” he wrote. “However, it is unproductive for everyone involved.”