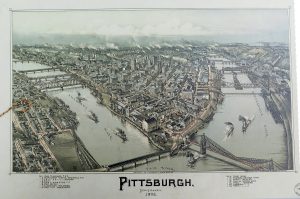

Pittsburgh’s skyline and rivers, as seen from Grandview Avenue at the Duquesne Incline © Karen Rubin/goingplacesfarandnear.com

I have come to Pittsburgh this first time to join the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy’s Sojourn three-day, 120-mile bike tour on the Great Allegheny Passage – a trail reclaimed from a former rail line that was used to carry the coal from the mines to the steel mills that is now playing a key role in revitalizing the small towns that had developed around coal. It is the foremost example of the transition of an economy and the society that it supports and how a city can go from grey to green. But I only have one full day, so I want my time to be as productive as possible.

And as authentic as possible, so I choose the historic Omni William Penn Hotel – a member of Historic Hotels of America – which celebrated its centennial in 2016 the same year as the city celebrated its bicentennial.

I start with the hotel’s concierge to get some ideas of how to organize my day in order to pack enough highlights that give me a real sense of this place – the things that are unique to the city.

She, in fact, epitomizes the story of Pittsburgh: her father worked in those steel mills of Andrew Carnegie and Frick, suffering the intense heat of a firey hell. There used to be steel mills lining the riverfront. She remembers how the pollution in the city was so thick, that you could not see the city below Grandview Avenue on Mount Washington ridge where I will be heading soon to take in the view. Her father died at an early age.

Today, the city’s main industries include academia, robotics, banking and finance and his daughter is now a concierge in this luxury hotel.

At its bicentennial in 2016, Pittsburgh boasted a population of 305,704; 2781 acres of city parks; 300 downtown restaurants; 31 skyscrapers; 90 neighborhoods; 24 miles of riverfront trails; 445 bridges (more than any city in the world) across three rivers.

Several of Pittsburgh’s unique attractions are associated with people that I had not realized were native sons: August Wilson and Andy Warhol. Indeed, the special history of Pittsburgh is preserved in the institutions associated with the Senator John Heinz History Center (yes, the ketchup company family), as I discover.

She loads me up with handy lists and maps, and draws a route for me, and I am on my way.

Walk with me…

The Monongahela Incline originally opened in 1870 (refurbished in 2015) and is the nation’s oldest cable car operation © Karen Rubin/goingplacesfarandnear.com

Around the Omni William Penn Hotel, a complete renaissance is still underway: modern skyscrapers in glass and steel reflect back on restored brick Victorians – not exactly a seamless melding of past and present, nor is history accurately reflected.

I head toward the Southfield Street Bridge, a jewel of a steel bridge with a walking/biking lane, that takes me over the Monongahela River, where on the shore, a lovely indoor Station Square mall has developed around what would have been a factory, and there is a lovely bike path. Across the street, is the entrance to the Monongahela Incline, a funicular that takes you up to the Grandview Avenue, aptly named for the grand view of the city from its heights, on Mount Washington, named for George Washington who surveyed the area from this place, choosing the location at the Point below for a fort.

It is one of two of the original 19 that used to run.

The Monongahela Incline originally opened in 1870 (refurbished in 2015) and is the nation’s oldest cable car operation. Its 35-degree grade makes it the steepest incline in the US; it travels the 635-foot length at 6 mph. It is operated by the Port Authority (so your bus pass works). Though the ride takes but a few minutes, it is so much fun. (portauthority.org).

The story of Pittsburgh is encapsulated from Mount Washington, named for George Washington who as a young man surveyed the area from this perch to choose a location for a fort. You gaze down at the expanse from viewing perches – how the rivers merge together, the skyscrapers and landscape. There are fascinating historical markers along Grandview Avenue that tell the story of steel and the critical role Pittsburgh played in the industrialization of the United States and its emergence, really, as a world economic power, and ultimately, “the Greening of Pittsburgh.”

Mount Washington was once called Coal Hill, the spot where the nation’s coal industry was born around 1760. “Here the Pittsburgh coal bed was mined to supply Fort Pitt. This was eventually to be judged the most valuable individual mineral deposit in the U.S.”

Another marker: “With its steel mills belching fire and smoke, Boston writer James Parton described the city as ‘hell with the lid off.’ Streetlights were often needed in the middle of the day to combat the haze of industrial smoke and grime. As recently as the late 1940s, visitors to Grandview Avenue had to strain to see the skyline through the haze.” Today, despite the clouds casting a grey pallor, I can still see the striking skyscape, and follow the outline of the rivers a long distance.

I stroll the avenue toward the next incline, the Duquesne, passing lovely Victorian homes and a library.

The Duquesne Incline opened in 1877 – it has quite an interesting display of historical photos and artifacts. It is operated by the Society for the Preservation of Duquesne Heights Incline. It travels the 793 length at a speed of 6 mph, bringing me back down to the riverfront and I walk across the Fort Pitt Bridge down into Point State Park.

Historical markers along Grandview Avenue make it easy to visualize Pittsburgh’s past © Karen Rubin/goingplacesfarandnear.com

What a jewel Pittsburgh’s Point State Park is, literally at the confluence of three rivers: the Monongahela River at one side and where the Allegheny and Ohio Rivers meet on the other. Its location made it critical to control over this territory and later, the industrial and economic development of the nation.

The Point offers beautiful park land as well as some of Pittsburgh’s most significant heritage sites.

You first come upon the Fort Pitt Blockhouse, built in 1764, the oldest building in Pittsburgh and the only remaining structure from colonial times. Inside this small, dark space, it gives you a glimpse of western Pennsylvania’s role during the French & Indian War and the American Revolution (admission is free).

What proves to be the highlight of my all-too-short visit to Pittsburgh is the Fort Pitt Museum (the newest member of the Senator John Heinz History Center, in association with the Smithsonian Institution), a modern, two-story, 12,000 square foot museum built on the site of Fort Pitt.

The presentations are absolutely thrilling in conveying how at a critical point in the settlement of the New World, this point was the epicenter of world-changing events.

“From 1754 to today, Fort Pitt has shaped the course of American and world history as the birthplace of Pittsburgh.”

The museum tells the story of Western Pennsylvania’s pivotal role during the French & Indian War, the American Revolution, and as the birthplace of Pittsburgh (William Pitt never actually visited). It offers extremely well crafted interactive exhibits, life-like historical figures, rare artifacts that let you come away with a new appreciation for the strategic role the region played.

Known as The Point, this was once one of the most strategic areas in North America, controlling access to Ohio and Mississippi Rivers and much of interior of North America; it was the intersection of cultural exchange with native people, and a departure point for settlers moving west.

I appreciated the balance in the presentations between points of view – the colonists (actually split between the British and the French) and the Indian tribes. There is a sensational video that presents the different perspectives (the Indians still come up short) – the different perspectives that the British and French brought, and the Indians whose culture did not acknowledge that a person could own land, but by this point, the Indian tribes had already had already become dependent economically on imported European goods.

Riding down the Duquesne Incline © Karen Rubin/goingplacesfarandnear.com

British and French clashed for control of the New World colonies constantly from 1689-1748: The French, most interested in trade, saw the Ohio River as a way to connect Canada and Louisiana and leverage their relations with Indians. The British, determined to control territory, also realized the strategic importance of this artery, “the Keystone of the Frontier.”

This becomes clear in a superbly produced video, “Whose Land?”: “The French couldn’t stand the British and the British wouldn’t rest until they owned [the territory].” Native Americans, were fully aware that they could not allow the Europeans to control the land, but they were caught in the middle – by this point, Indians were dependent upon trading for manufactured goods.

“The Indians negotiated with weight and authority. They had a powerful confederacy

Iroquois – Seneca, Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida. They had sophisticated government, freedom, a rich culture, complex trading relations. Agriculture was central but they did not have private ownership. They took a cue from nature. They enjoyed trade – and were heavily dependent on some European goods, and even took up the European religion, but kept their own ways.”

“God created all people but different,” an Indian chief said in 1742.

With French dominion on one side of the river and English on the other, where does the Indian claim lie?

George Washington, a 21-year old major in 1753 with experience as a surveyor, was given a mission to explore to Fort LeBoeuf and recommended the site for Fort Prince George.

Washington “had no diplomatic experience, and couldn’t speak French yet he was selected to bring message to French. He was selected because of his close connection with Ohio corporations and other Virginian land speculators in land. He knew ‘the West’.”

In 1754, Fort Duquesne (renamed Fort Pitt when the British took over), was the largest French military installation in Ohio, and evicted the Virginians.

Costumed docent sends school kids off on a scavenger hunt at the Fort Pitt Museum © Karen Rubin/goingplacesfarandnear.com

William Pitt, for whom the fort is named, never came to the colonies. The city originally was called “Pittsboro”. The Fort – perhaps because it was so foreboding, was attacked only once, during Pontiac’s War of 1763.

Its location made Pittsburgh a boom town. The Ohio River carried 18,000 settlers through in 1788. The population of Pittsburgh, just 150 in 1780, grew to 4,800 by 1810, making it the third largest in Pennsylvania after Philadelphia and Lancaster.

Its economy developed from coal mining, glass making, and boat building, fueling the nation’s industrial and physical expansion. The city was incorporated in 1816.

When I visit the museum, there are a number of school groups coming through. The school kids are sent out in teams on a scavenger hunt by a docent in period dress. What surprises the kids the most? That the Indians were not as primitive as they expected, she tells me. Indeed, many are pictured wearing European-style clothes and served in the military. By this point, the Indians were part of the world economy – the Indians traded their furs for items from as far away as China; the European traders were like Walmart to them, bringing manufactured household goods. For the first time, I understand why the Indians did not kick the Europeans out when it was clear they were setting up outposts.

As I explore the exhibits, I learn of what may have been the first incidence of germ warfare: in 1763, an Indian trader, on orders from Ft. Pitt, is alleged to have given Indians two blankets and a handkerchief from the fort’s smallpox hospital.

During my visit, I am fortunate enough to see a special exhibit (no longer on view), “Captured by Indians” that introduces me to an issue that I knew nothing about before, that makes you really think.

The fascinating display is about European (white) colonists as well as slaves who were kidnapped by Indian tribes. The exhibit did not disguise the brutality, but most fascinating is that the individuals (who often were young when they were taken captive), particularly women, once they survived the arduous journey and a literal gauntlet (to weed out the weak), were adopted into the tribe, treated as equals, and generally had a better life than the colonial settlements they came from, especially if they were indentured servants or slaves or women, to the extent that when they had the chance to be “freed” and be returned to their community – such as in a hostage exchange – they would refuse and even escape back to the tribe.

The presentation, the artifacts and the connection to people living today, descendents of those people, is utterly fascinating.

“During the turbulent decades of the mid-18th century, thousands of European and African settlers were captured by American Indians whose dwindling numbers forced them to adopt non-Indians in an effort to survive. The subsequent experience of captivity and adoption forever altered both the captives and their captors as identities shifted, allegiances were tested, and once-rigid lines between cultures became forever blurred.”

Fort Pitt Museum tells the story of Western Pennsylvania’s pivotal role during the French & Indian War, the American Revolution, and as the birthplace of Pittsburgh © Karen Rubin/goingplacesfarandnear.com

Fort Pitt Museum tells the story of Western Pennsylvania’s pivotal role during the French & Indian War, the American Revolution, and as the birthplace of Pittsburgh © Karen Rubin/goingplacesfarandnear.com

The exhibit, with artifacts specially gathered, draws upon documentary evidence gleaned from 18th and early 19th century primary sources, dozens of rare artifacts, and a wide array of imagery, to examine the practice of captivity from its prehistoric roots to its impact on modern American Indians and other ethnicities.

The captives taken in brutal raids, massacres and abductions were mainly of young who were physically fit and could assimilate and women who would be married off and bear children. They would size people up during the raid, and decide who to take, then put them through a kind of gauntlet (as well as an actual one at the end), to weed out the weak or uncooperative.

The exhibit tells the story through the experiences of real-life captives, and in stunning displays including three life-like vignettes that portray John Brickell, a local boy captured just a few miles from Fort Pitt at age 10; Massy Harbison, who heroically saved the life of her child after escaping from her captors; and the Kincade family, who were reunited on the Bouquet Expedition in 1764

I am amazed to learn that many of the captives preferred Indian society: Colonial society could be brutal, especially for those at the bottom (like slaves and indentured servants and poor), women were property of husband. But in native society, they had equality. “Many adopted captives lived and died among chosen people.”

At the end is a large wall of photos of people today who trace their origins to these captives.

“While many captives were returned to the society of their birth after months or years among the Indians, many others lived out the remainder of their lives with their adoptive people. Today, the descendants of captives represent a wonderfully diverse cross section of American society. In many cases they are alive today because of crucial decisions made in an instant, two centuries ago. They represent the living legacy of captivity, reminding us not only of our connection to the past, but also to the future.”

In summer, the Fort Pitt Museum offers living history programs and reenactments –with staff dressed in period costumes, firing off cannons, playing fife and drum, doing carpentry.

Fort Pitt Museum (open daily, 10 am – 5 pm, $5/adults, $4/seniors/ $3 students and children 4-17), 101 Commonwealth Place, Pittsburgh, PA, 15222, 412-281-9285, www.heinzhistorycenter.org/fort-pitt/

My full-day’s walking tour also includes the National Aviary (www.aviary.org) and the Andy Warhol Museum, which is one of the Carnegie Museums (The Andy Warhol Museum, 117 Sandusky Street, 412-237-8300,www.warhol.org ).

I top my walking tour off with a stroll into the Strip District, once an industrial section, now full of markets, restaurants, shops of all kinds and ethnicities, before walking back to my hotel the Omni William Penn, a member of Historic Hotels of America.

Unfortunately, I don’t have enough time to visit the Heinz Center before it closes for the day. Pittsburgh is definitely worth a return visit (Heinz History Center, 1212 Smallman St., 412-454-6000, www.heinzhistorycenter.org).

For more information, contact Visit Pittsburgh, 412-281-7711, 800-359-0758, 877-LOVE PGH (568-3744), info@visitpittsburgh.com, www.visitpittsburgh.com.

© 2017 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com, www.huffingtonpost.com/author/karen-rubin , and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Send comments or questions to FamTravLtr@aol.com. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/NewsPhotoFeatures