Aspects of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur have always appealed to me. I offer my comments mindful that, for religious Jews, there are many dimensions to the 10-day period of the High Holidays that are not included in this discussion.

Folks in our general society often see a new year as a time for reflections and resolutions. Indeed, for Jews, this Day of Atonement is the culmination of the launching of their New Year 5780.

I have commented to friends that all of us could benefit from regular days of atonement, some of whom have then reminded me that Catholics have a sacrament of confession and are urged to engage on a weekly basis.

Many groups foster regular reflections. The annual Odwira Festival (Oct. 12) in Queens indicates that “the community is expected to make amends, settle disputes, release grudges – then receive cleansings. This opens the way for growth, progression, and new blessings. We are rejuvenated, refocused.”

I am especially attracted to some Jewish references for Yom Kippur “to atone” (or cleanse), as the day seeks a focus on both “personal and national sins.”

Yom Kippur and other occasions of reflection and redirection can have even greater benefits as one looks beyond the personal to our social responsibilities. Clearly, for Jews and others, rituals can serve as annual dates to mark engagement, participation with others (thus, being strengthened by a sense of community), reinforcement of historical memory, and good conduct.

The question then emerges: how do we proceed after seeking atonement? Will religious folks have more success in keeping vows for change than secular folks do each New Year? How many penitents will seek to connect their personal improvement with the improvement of their nation and of all nations?

The challenges for personal enhancement are daunting by themselves; can reflective and penitent folks be encouraged to become engaged in sustained efforts to improve their own lives, as they also think nationally and globally for human rights? In short, how many of us can move from atonement to “le vertu,” what Montesquieu described as “the willed initiative”?

Just to become aware of our shortcomings is a positive if that cleansing reflection motivates us to try to do better with others and for society. But what factors are most likely to foster le vertu for weeks, for months, of action? As Dr. King once observed, most people are capable of a spasm of virtue, but their sustained goodness is necessary for transformational changes.

Fitness studies show that folks progress when they have partners who share their commitment (often having a mentor is an added boost). Certainly, temples and other religious groups, as well as voluntary associations (celebrated by Toqueville nearly two hundred years ago as distinctive American endeavors), can bring people together for focused goals and demonstrate the satisfactions of shared endeavors to do good (not merely to do well).

Weeks of action are likely to be successful when they are based on written goals when there are regular review processes to take stock of how things are going, when leadership is widely shared, and when constructive critical views are invited.

Individuals who come together to do good need not be solemn; social opportunities with each other – picnics, festivals, music, theater outings, book clubs, square dancing, and myriad activities can deepen bonds of affiliation.

Building from days of atonement – and more frequent points of reflection – individuals and groups benefit from the confidence that their sustained commitment can make a difference.

A guide for all of us was posted Sunday on a large bulletin board at the Holocaust Memorial and Tolerance Center of Long Island:

“I am only one, but I am one,

I cannot do everything, but I can do something

And I will not let what I cannot do interfere with what I can do.”

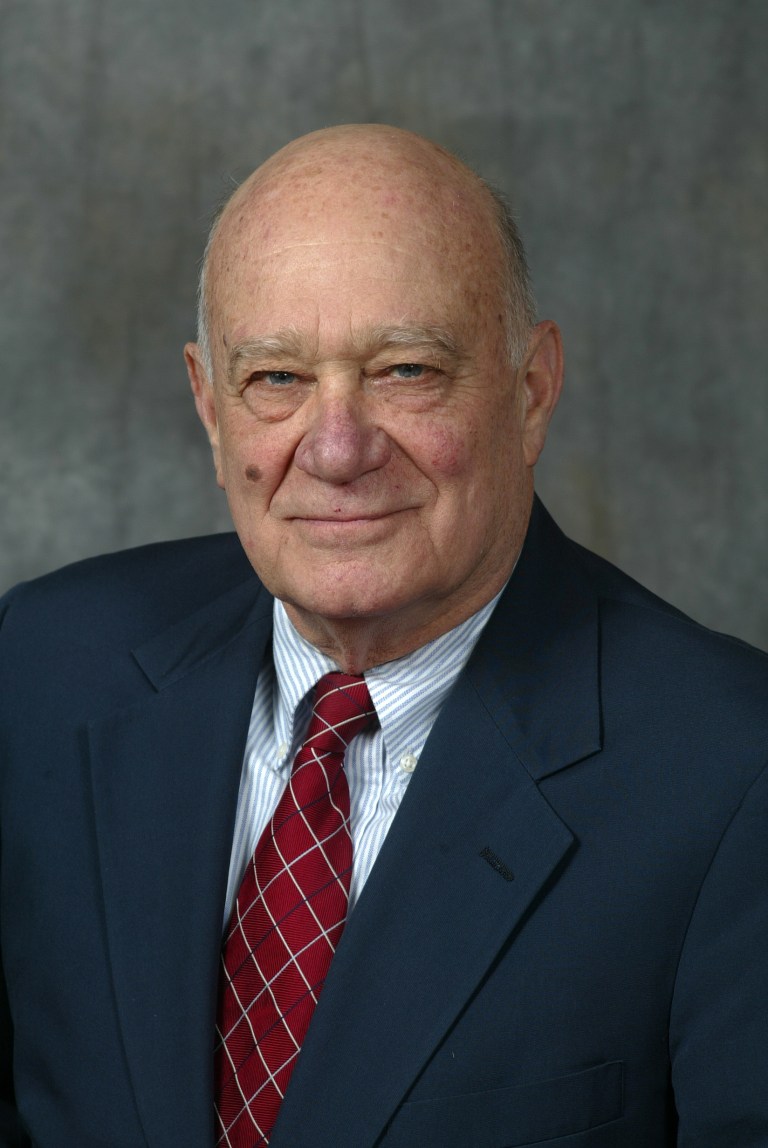

The statement from Edward Everett Hale in the 19th century captures the 21st-century spirit of Ben Ferenc, who was Sunday’s focus in the documentary film, “Prosecuting Evil.” The large crowd of Long Islanders appreciated Ferenc’s role as a Nuremberg prosecutor and, especially, his expanding advocacy for nonviolence, for justice, and for peace initiatives in the U.S. and around the world.

During a highly informative question and answer segment, St. John’s University Professor of Law John Q. Barrett deepened appreciation for Ben Ferenc’s ongoing activism. As individuals seek pathways to protest and reform, Mr. Barrett urged that they “regard Ben Ferencz primarily as a teacher,” and that they benefit from consulting his website (benferencz.com)

Now, at age 99, Mr. Ferenc regularly calls on everyone to contribute to advancing human rights, from weeks of action to decades of activism.